The Magazine of The University of Montana

Esprit de Corps

Devotion, Honor, and Pride Still as Strong as Ever as College of Forestry and Conservation Celebrates 100 Years

Story by Chad Dundas Photos courtesy of Archives & Special Collections, Mansfield Library, The University Of Montana

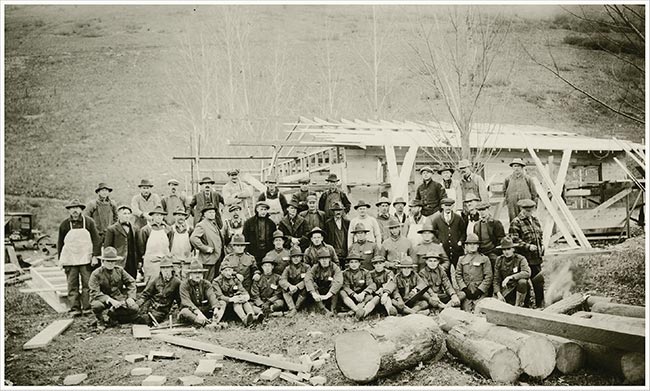

Top: Construction of the original Forestry Building, known as “The Shack”

Photo: Melville Leroy Woods Album

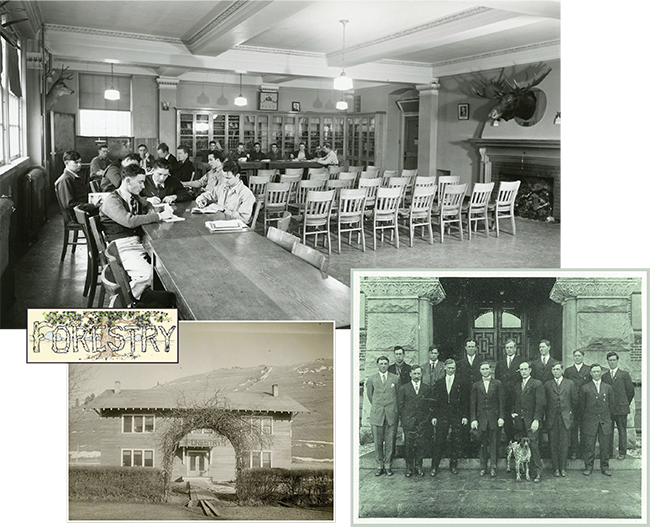

Clockwise from top: Students meet in the Forestry Club Room in 1938.

Members of the 1913 Forestry Club

The entrance to the “The Shack,” ca. 1919

The 1915 Forestry logo

94.1835, Mss 249, Rollin H. McKay Photographs; The Sentinel, 1913, page 62; Courtesy of UM College of Forestry and Conservation; UM95-1219; The Sentinel, 1915, page 37 Photo: rg6b2f21shack, RG 6, UM Photographs by Subject

On the 100th birthday of UM’s College of Forestry and Conservation, Dean James Burchfield sits in his office talking about outer space.

“I don’t know if you’ve read Tom Wolfe’s book The Right Stuff,” he says, referencing the landmark account of the early American space program that stoked imaginations for a generation of young people upon publication in 1979. “Before I became a forester, I wanted to be an astronaut. It was because I saw it as a really great challenge, and I wanted to challenge myself.”

Burchfield makes this statement as part of a longer answer about why his particular department inspires such loyalty in its students and faculty. On its face it seems like an odd association for the head of one of UM’s oldest professional schools, one that generally prides itself on notions of practicality and utility. Perhaps though, it’s as good a description as any of the kind of person drawn to forestry, and as good an explanation of how during the past century the college has become a leader in natural resource management.

The 1918 Foresters’ Dance Card cover

Maybe what you have here is a department full of people who want so badly to make a difference, they’d be willing to leave the Earth to do it.

Ironically, like Burchfield, most end up finding the biggest challenges of all right here under their feet.

“I think our work is noble work,” he says. “I believe that living on this one little blue planet and figuring it out is the great human challenge. We have a lot of work to do. We have problems that are very, very big, and we [in forestry] take on the mantle of those who are responsible for helping to find some of the solutions. It’s an idealistic profession. It’s a profession where you’re working on things you believe are truly important.”

March 21, 2013, is a typical spring day in Montana—snow one minute, sunshine the next. Just a few minutes earlier, Burchfield was embroiled in the day-to-day operations of his office, which he describes as coordinating “research projects the faculty are doing, indirect cost rates, budgets, personnel, more budgets.” The ninety-sixth annual Foresters’ Ball is tomorrow night, and at the University Center, students in flannel, hardhats, and Carhartt pants man an information booth that boasts a chainsaw as its primary decoration. Outside the Forestry Building, classes are in session as small groups huddle around the trunks of trees—some hauling large plastic tanks of water, others brandishing hammers or rulers.

In other words, the forestry college appears to be in fine shape as it crosses over the century mark. After experiencing a slight decline from 2004 to 2007, enrollment is back up to about 880 students. That includes around sixty graduate students and sixty Ph.D. candidates in addition to the 760 working on undergraduate degrees in the college’s five majors: forest management; parks, tourism, and recreation management; resource conservation; wildlife biology; and wildland restoration. More than 300 of the students are female, a number that has grown significantly since the program began. Burchfield estimates the faculty now brings in between $6 million to $8 million a year in new sponsored research while instructing students in an ever-evolving curriculum that prepares them for the sometimes grueling demand of working outdoors.

“You’re going to get challenged here. You’re going to get pushed,” Burchfield says. “If we’ve got a motto, it’s ‘Can you keep up?’ There’s a lot to do here that’s difficult. You have to be a scientist—this is a Bachelor of Science degree … [and] we expect our students to be able to function in the field. We want people who hire our students to be able to give them the keys to the truck and say, ‘Go do it.’ Not only will they go do it, but they’ll do it extremely well.”

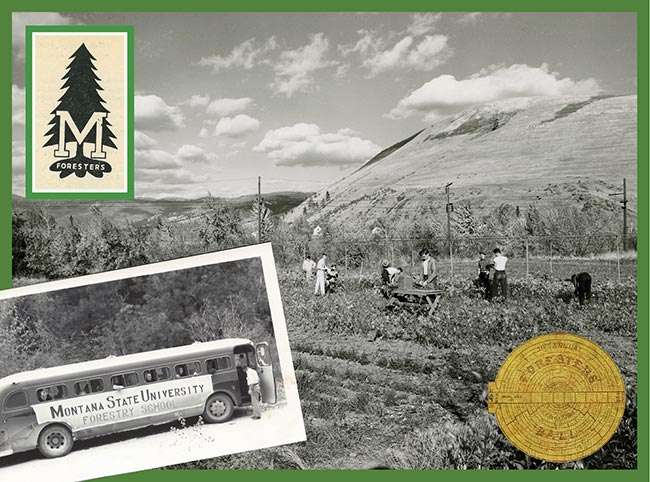

Bottom Left: In a chartered bus, the 1941 range management seniors traveled 3,196 miles in eighteen days from Montana southward to the Mexican border, stopping in places such as Zion National Park, the Painted Desert, and other colleges and universities along the way.

Clockwise from top:

The Montana Forestry Club Handbook logo, 1954-55

Students digging and grading in the nursery

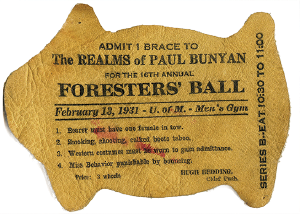

A ticket to the thirty-first Foresters’ Ball

Clockwise from top: Page 4, University Publications; rg6b2f22nursery2, R.H. McKay, RG 6, UM Photographs by Subject; Courtesy of UM College of Forestry and Conservation; Courtesy of UM College of Forestry and Conservation

The first rangers came to UM in January 1909, four years after the creation of the U.S. Forest Service and a bit more than four years before the Montana Legislature officially authorized the School of Forestry. Their arrival was not without controversy, as the U.S. Treasury Department cut the program’s funding near the end of 1910. The student newspaper cried: “Foresters Declared Illegal Students,” and the fledgling school might have perished entirely had University President Clyde Duniway not stepped in and secured the funding to keep it open.

On March 21, 1913, the Legislature gave its stamp of approval, and during the next few years, the school buttressed its ranger program with expanded courses on botany and biology. Even as the college evolved, however, the primary focus remained on providing the Forest Service with trained woodsmen. During its first few decades, the curriculum adhered to a decidedly technical bent.

“At the time, there was the thought that foresters could do anything,” Zane Smith says about the road-building, ax-wielding, altogether ranger-centric education he received while attending UM in the early 1950s.

Now eighty years old and a self-described “third-generation forester” who had a thirty-four-year career in the Forest Service, Smith terms his years on campus as a time of great transition for the forestry program. The faculty’s old guard was giving way to new blood, and student organizations boasted numbers and social clout rivaling the University’s Greek societies. The education was rigorous, but when they weren’t chopping or scouting or measuring, forestry students reveled in campus life, which Smith says prepared him for the real world as much as anything.

“I thought it was a huge advantage to be on a liberal arts campus as a forestry student,” he says. “It gave you the opportunity to rub shoulders with law students and musicians and English students. I think that’s still true in some respects.”

By the early 1970s, the passage of legislation such as the National Environmental Policy Act and the Clean Water Act represented a dramatic shift in the national land-management plan. UM’s program, which had been trending toward including more elements of conservation and natural science anyway, moved quickly to evolve with the times.

A ticket to the sixteenth Foresters’ Ball

Courtesy of College of Forestry and Conservation

“There was a sense that change was afoot ... the ranger days were coming to an end,” says George Hirschenberger, who worked for the Bureau of Land Management in numerous Montana cities after graduating in 1972. “By the time I left, NEPA and a bunch of other policy acts had been passed that kind of set the stage for what we are now experiencing in terms of federal land management.”

UM’s greatest contribution to that evolution arguably came in the form of the 1970 Bolle Report, a thirty-three-page study of federal clear-cutting practices in the Bitterroot National Forest commissioned by Montana Senator Lee Metcalf. The report, bearing the name of UM forestry Dean Arnold Bolle, charged the government with poor land-management practices, asserting that wildlife, watersheds, and preservation were “after-thoughts” compared to “the single-minded emphasis on timber production.”

The report marked the first time the college had publicly broken ranks with Forest Service dogma. It constituted what UM natural resource policy Professor Martin Nie calls “a major flashpoint in American environmental history” and spurred considerable changes to America’s natural resource laws.

“This school had a huge impact in passing the latest, most significant piece of forest management legislation in the country,” Nie says. “The National Forest Management Act from 1976 was in many ways catalyzed by work done in the Bolle Report.”

The publication of the Bolle Report in the Congressional Record is frequently mentioned not only as a major signpost in the history of forestry, it may well effectively represent the beginning of the modern forestry college as we know it today.

The most obvious bit of modernization done to the forestry school during the past ten years was a change to the sign outside its ninety-two-year-old building.

In April 2003, the school officially became the College of Forestry and Conservation, a switch that reflected the significant pedagogical strides of the previous few decades. As the country’s forest policies changed and the science associated with natural resource management continued to advance and improve, so too did the school itself, adding avenues of study, areas of emphasis, and new majors.

“That’s the thing I think makes this college so interesting,” Nie says. “If you just went down this hallway, you’d see we have a fire ecologist, a forest ecologist, a sociologist, a recreation person, a policy person, and writing professor. It’s that eclectic.”

As the school moves into the future, Burchfield has his eye on international expansion. Relationships in places such as Bhutan, Chile, and India are being fostered, and he hopes carefully cultivated partnerships with institutions in Peru and the Philippines will follow. This spring, UM forestry students began a program planting trees in Guatemala.

Students identify various pinecones for a class. Photo: UM95-1215

At home, Burchfield says the school will continue working on the real-world problems facing people in Montana. It’s currently engaged with the city of Missoula, looking for solutions to the town’s urban deer issues and matters of statewide concern such as climate and fire research.

In September, the college will hold an official celebration of its centennial, and alumni like Smith and Hirschenberger will no doubt be there to commemorate its long, proud history. Even as it turns its eye to the next challenge, the college stays grounded in a bedrock of love and respect for the outdoors. As much as the science and bureaucratic policies change, students still flock to Montana for the same reason today as they did 100 years ago. To know what that reason is, all you have to do is look out the window:

Wilderness.

“It’s the center of the universe in a way; it really is,” says Nie. “You can’t go a day without reading a federal land story on the front page of the paper. We’re surrounded by federal land [and] wildlife issues. That’s why people want to come here.”

To learn more about the history of UM’s College of Forestry and Conservation, visit http://exhibits.lib.umt.edu/forestry/history/cfc for an online exhibit produced by the Mansfield Library.

Email Article

Email Article